Sino-US geopolitics are upping the risk ante for firms and investors

The edgy relationship between China and the United States and other liberal leaning democracies is undoubtedly the principal drama of this part of the 21st century. In what is an existential, values-based struggle, the main protagonists have locked horns in the sensitive spaces where economic and national security meet. The NATO summit in June 2021 sought to address China as a security challenge for the first time, describing its goals and assertive behaviour as presenting ‘systemic challenges to the rules-based international order and to areas of relevance to alliance security’.

General Secretary Xi Jinping has said that China is well placed to exploit a historic opportunity in contemporary world affairs in which ‘the East is rising and the West is declining’, that time and history are on China’s side, and that no one should doubt China’s invincibility. In Beijing, the consequences of America’s painful withdrawal from Afghanistan have only corroborated this view.

In the United States, President Biden nonetheless sees the end of the Afghanistan involvement as clearing the decks to focus more on China. The passage of the Strategic Competition Act 2021 provides for a multitude of measures designed to further US objectives as they relate to national security, human rights, democracy, intellectual property, and data privacy. It is comprehensive legislation that seeks, among other things, to counter the expanding global influence of China, with the explicit policy goal of sustaining America’s global leadership role in a system where China is ‘ leveraging its political, diplomatic, economic, military, technological, and ideological power’ in ways that are ‘contrary to the interests and values of the United States, its partners, and much of the rest of the world’.

Corporations and investors are consequently being drawn into the murky world of geopolitics, where they have to watch out for new commercial and political risks and conflicts of interest, which may be sudden. They may be forced to choose whose rules to obey, and whose to flout.

Managing risk in foreign countries goes with the turf of foreign direct investment and buying foreign financial assets, but however adept investment professionals and corporate managers are at assessing and mitigating financial risk, there is little question that political risk is altogether a different challenge. Domestic developments in the United Sates and China and complex international relations matters are likely to make this challenge increasingly complex.

More repressive domestic conditions for private firms

China’s anti-corruption campaign, which General Secretary Xi Jinping inaugurated in 2012, has incarcerated or otherwise punished almost 3 million people. The vast majority of cases has applied to so-called ‘flies’ or minor party officials for disciplinary offences, but the campaign has also ensnared some ‘tigers’ too in the party, armed forces, state enterprises, finance and other sectors for both discipline and corruption offences. In more recent years, anti-corruption has broadened out to include company executives and entrepreneurs. Private firms in China, long regarded as the leading edge of China’s economic eruption, are still viewed as important but no longer revered or trusted politically as the focus has shifted increasingly towards the state sector in the economy, and strengthening the role of the Communist Party in operational management and business decision-making.

The orchestrated deposition this year of Jack Ma, celebrated entrepreneur and founder of Alibaba, may not have been down to corruption as such, but served as a reminder to businesses of the arbitrary nature of contemporary government and governance. The regulatory authorities were certainly anxious about the risks posed by Alibaba and its Ant Group affiliate to regulatory arbitrage and to the loss of state control over data, financial stability, and security from Ant’s fintech activities. Yet, the involvement of Xi Jinping in the abrupt cancellation without notice of Ant’s mega-IPO late last year, and the treatment of Ma subsequently, also suggest strongly that power and authority were also important factors in what has become a broad crackdown on technology, data and finance platforms.

Other such firms or those at the cutting edge of the digital economy such as Tencent, Xiaomi, Pinduoduo, Baidu and Meituan have all been obliged to pay attention and comply with a more state- and party-centric governance structure. All saw their stock prices fall sharply in the wake of the Alibaba clampdown, and were still about 40 per cent of earlier year highs, even after a bounce in the late summer. Sentiment was adversely affected, moreover, by the Cyberspace Administration of China’s announcement of an investigation of, giant cab hailing firm, Didi Chuxing and its demand that Didi apps be withdrawn straight after the company’s IPO in New York in June. Several other IPO’s by Chinese entities were pulled in the wake of these developments, as China’s regulatory authorities vowed to exercise much tighter scrutiny and control over future foreign listings. It would be no surprise if this end up in prohibition, and retraction of the variable interest entity structure for foreign listings.

The regulatory crackdown on firms was broadened out to include the private tutoring, gaming, video streaming, and social media sectors, while more restrictive conditions have been announced for cloud computing firms, real estate companies and landlords and other activities as China’s government sought also to re-emphasise the policy of ‘common prosperity’ to arrest serious inequality. A spate of measures is expected involving some elements of new taxation and perhaps more assertive redistribution.

For China, public ownership or control over platforms in the digital economy, and stricter rules as provided by the China Securities and Privacy Laws, and anti-trust, anti-monopoly and data and cyber security regulators, are the only ways to tame capital and ensure it is politically subservient.

For the US, this backdrop is precisely why future listings are unwelcome, and why even existing ones are at risk, including under the Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act 2020.

Laws in Beijing and Washington look increasingly as though companies and investors are going to become conflicted in the conduct of their governance.

Chilly geopolitical winds for foreign firms and investors

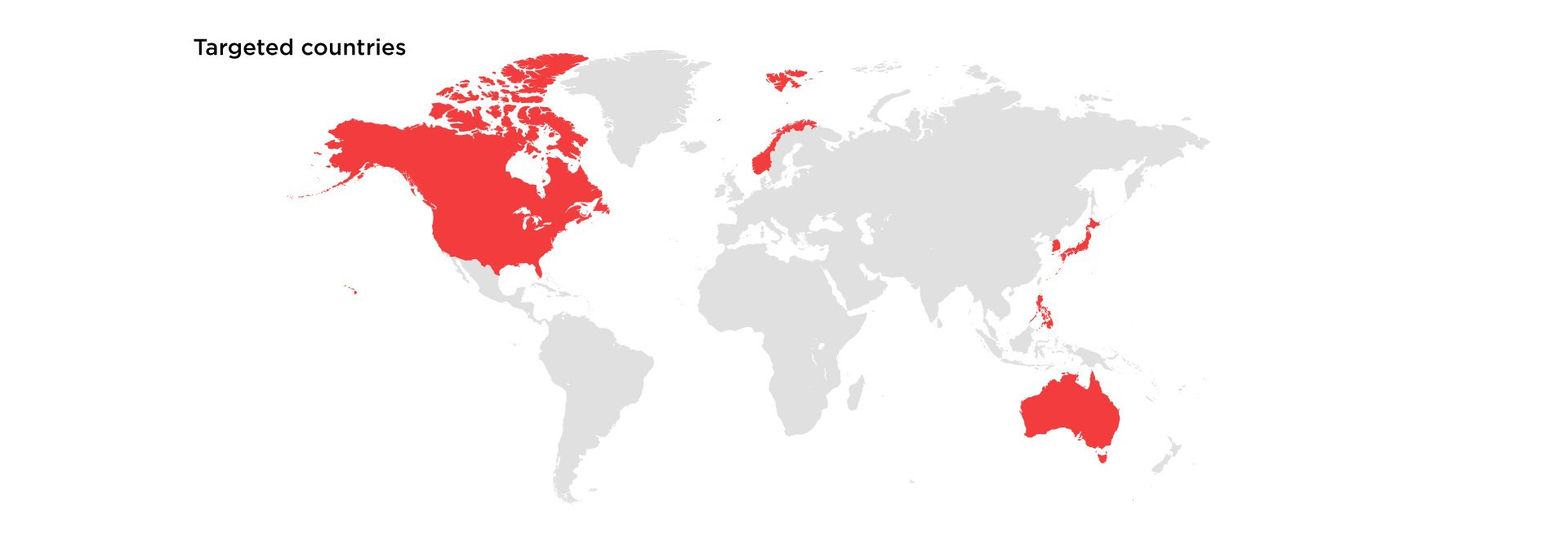

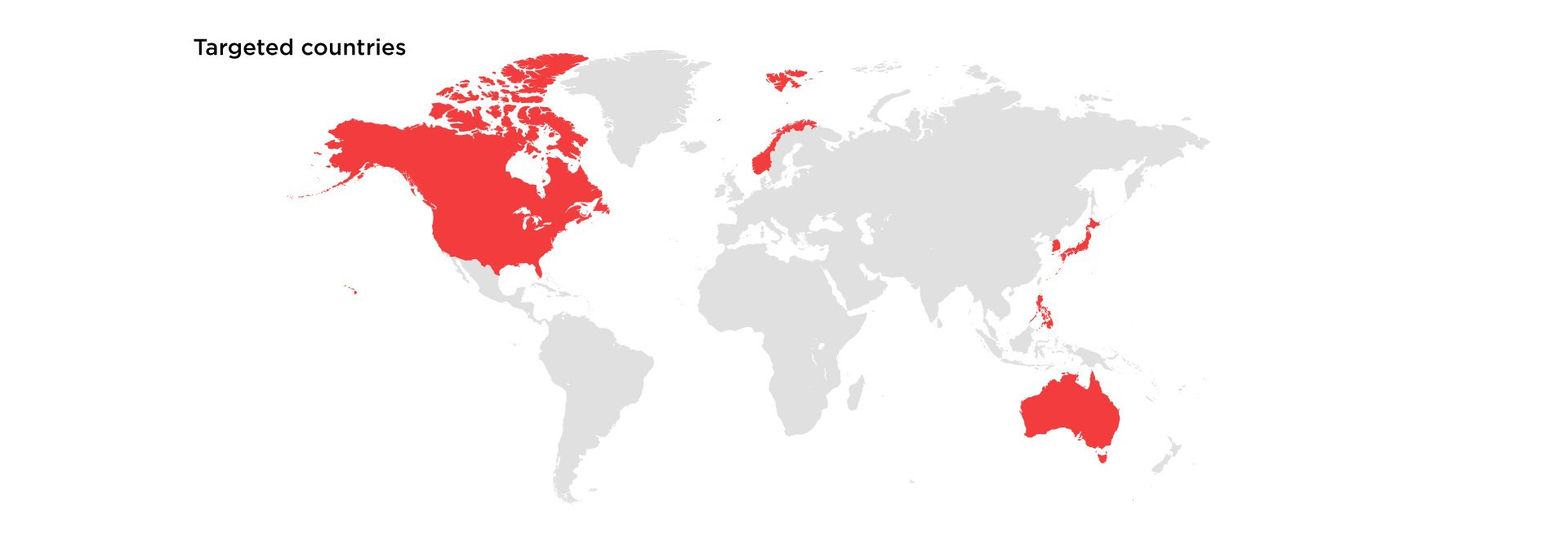

China has form over the last decade when it comes to targeting firms of states where it has had disagreements, for example, Norway, the Philippines, Japan, and South Korea. More recent actions have been remarkable, especially as they pertain to Australia. There have also been campaigns against airlines and other firms that had referred to Taiwan as not part of China, and in 2020, Cathay Pacific was pressured to fire staff who had participated in pro-democracy protests. In 2021, some foreign companies in Xinjiang were singled out to remove website denials about the use of forced labour and sourcing of cotton in the province. Two Canadian citizens, Michael Spavor and Michael Kovrig are now spending a third year in prison on charges of ‘espionage’, as retaliation for the detention in Vancouver of a senior Huawei executive, pending extradition by due process to America. Several journalists and others working for media organisations have been expelled or arrested.

Businesses and investors now have to be well versed in the language and implications of export controls, national security interests in foreign direct investment, lists of companies forbidden to sell or trade certain products, financial restrictions, and the sanctioning of individuals, and business and other entities.

Bilateral trade tariffs now seem rather dated as measures and counter-measures have moved on to restrictions on the terms under which companies can engage with one another, especially in technology and telecommunications. The US has a lengthening ‘entity list’ of Chinese companies and other organisations with which US firms are restricted from doing business unless they have license. Restrictions apply to Chinese companies with links to the People’s Liberation Army, the implementation of repression in both Xinjiang and the National Security Law in Hong Kong, and those militarising disputed islands in the South China Sea.

A whole-of-government infrastructure of restraint has been assembled in Washington, including the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security, which oversees technology and export controls; the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control which administers sanctions, including on individuals and entities in Xinjiang and Hong Kong; the Justice Department’s National Security Division, which authorises criminal prosecutions in relation to theft of trade secrets and intellectual property; and the interagency Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, which polices foreign direct investment, now with a wider brief, following the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernisation Act 2018, and the Strategic Competition Act.

In 2021, in further tit-for-tat sanctions, the US, UK, EU and Canada imposed new measures against individuals and entities deemed to be responsible for genocide in Xinjiang, to which China retaliated by imposing its own sanctions, including on European Parliament members, EU officials and a major China think tank and its employees in Berlin, and also UK parliamentarians, and other UK individuals and entities. In the wake of China’s sanctions, the European Parliament voted to freeze the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment, bilateral Sino-EU investment treaty, signed to great fanfare in late 2020.

Earlier this year, China’s Ministry of Commerce introduced Rules on Blocking Unjustified Extraterritorial Application of Foreign Legislation and Other Measures, designed to help both local and foreign firms nullify the effect of US export controls and sanctions that apply to companies outside China. These complement the previously passed Export Control Law, which restricts the sale of certain products to foreign entities, and establishment of Provisions on the List of Unreliable Entities which restrict business with foreign entities that are deemed harmful to China or its agencies and corporations. In June, the Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law was passed, ostensibly providing a legal umbrella for firms operating in China to appeal against having to comply with third party sanctions or face penalties if they do. In practice, these laws and regulations may be intended principally, not so much for rigorous implementation, but to force companies to comply with what Beijing wants. We should assume, though, there is no risk of test cases to prove a point.

Foreign investors have been drawn to China’s bond and equity markets by choice through active managers, passively as the weightings of Chinese financial assets in global benchmark bond and equity indices have risen, or through exchange traded funds. Foreign portfolio investment into China rose by over 40 per cent in the year to June 2021, reaching over $800 billion.

For institutional investors at least, the promise of growth and expanding market size has been sufficient until now to compensate for drawbacks such as the lack of transparency in company reporting and prospectuses, inadequate pricing of risk, unreliable credit ratings, and a rising number of credit events. We can imagine though that retail investors and perhaps in due course institutions will come to reconsider the nature of their exposure to Chinese firms and assets. At the very least, they will have to factor in valuations that reflect new political risks and the volatility of political and regulatory decision-making in both Beijing and Washington.

Financial sanctions have been implemented against Chinese officials and entities in Xinjiang and Hong Kong. Federal pension funds have been banned from investing in Chinese stocks. By executive order, US investors are required to divest from about 35 Chinese firms tied to the People’s Liberation Army and other surveillance agencies, and over 200 Chinese firms listed on US exchanges have been given limited time to comply with US accounting standards or be delisted under the Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act 2020.

Conclusion

It is at present impossible to envisage how or when there might be a material improvement in Sino-US relations. Trade, technology sector, and financial and travel sanctions and restraints have already been used against entities and individuals, sometimes as signalling devices, and sometimes in anger, but with real world consequences for firms and markets, nonetheless.

For the time being, the US should be expected to want to exploit the leverage it holds over China in respect of both technology and finance. China is reliant on US technology firms and imports, and the US dollar remains the world’s principal reserve currency, used for most external funding and financing, including by China. If sensitive issues, for example in the South China Sea or Taiwan, were to deteriorate markedly, we should expect the US to use these tools more intensively.

This reality, though, is also driving Beijing to carve out space for itself beyond the reach of US financial power, by trying to construct with Russia and other nations alternatives to US dollar payments and clearing structures, and by internationalising the yuan along with its own digital currency. To these ends, it may act to both nurture and penalise, even though these goals are fraught with contradictions, and are barely achievable as things stand.

For the foreseeable future, businesses and investors will have to assume that the regulatory and financial environment will be hostage to escalation and volatility.

George Magnus is an independent economist and commentator, and Research Associate at the China Centre, Oxford University, and at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London. George was the Chief Economist, and then Senior Adviser, at UBS Investment Bank from 1995-2012. His current book, Red Flags: Why Xi’s China Is in Jeopardy was published in September 2018 by Yale University Press.